AUTHOR: Andrew Pengelly, PhD

Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav) S.T. Blake Family: Myrtaceae

(NOTE: There is a PDF version of this detailed post available to download HERE.)

Melaleuca – from the Greek melas, meaning black or dark, and leucon, meaning white. This meaning is rather obscure, but it is suggested that it refers to black marks on the white trunks of some species due to fire exposure.

Quinquenervia – from the Latin quinque, five, and nervus, nerve, in reference to the five nerves or veins on the leaf blades.

Common names: Coastal paperbark, broad-leaved paperbark

Overview

M. quinquenervia is the most widespread of several Melaleuca paperbarks from the coast and sub-coastal regions of Eastern Australia. The medium-size tree bears aromatic leaves and profuse bottle-brush flowers.

Two main chemical varieties of essential oils are produced from the leaves, being labelled “nerolina” which is high in the sesquiterpene alcohol nerolidol, and “niauoli” which is high in 1-8 cineole. Both essential oil types are highly regarded in aromatherapy. In addition, the leaves are a rich source of polyphenols, triterpenoids and sterols.

This paperbark prefers to grow in wetlands but is well adapted to cultivation in a wide range of situations. Its’ blossoms are a major attraction for birds, bees and fruit bats.

Description

Tree up to 15m high, with characteristic white papery bark. The bark has many layers and a spongy texture. Leaves are alternate, lanceolate to elliptic, to 70 mm long and 24 mm wide, with an obtuse apex on long petioles.

The leave blade is flat, slightly leathery, and characterised by 5 prominent longitudinal veins. Leaves are aromatic when rubbed.

Inflorescences are bottlebrush-like spikes, mostly 2–5 cm long. Flowers occur in threes within each bract, creamy in colour. Petals are obovate in shape, 2–4 mm long and deciduous. The stamens are the most prominent aspect of the flower, they are 8–12 mm long, 6–10 per bundle, with creamy white anthers. There are red flowering forms at Hunter Region Botanical Gardens.

The dry fruiting capsules are broad-cylindrical, 4–5 mm diameter. The capsules may remain closed for years, opening to release their seeds when conditions are most favourable.

In waterlogged and flooded areas this species forms adventitious aerial roots. It is a fire-prone species, since the papery bark readily catches alight, spreading flames to the canopy of leaves which are rich in volatile oils.

M. quinquenervia in a Brisbane garden and a typical wetland in New South Wales

Photos by Andrew Pengelly

Distribution

Wetlands and lake margins of the east coast, from Botany Bay to Cape York Peninsula, also in parts of Papua New Guinea, Indonesia and New Caledonia. It tends to grow in pure stands. In New Caledonia the species grows on elevated, well-drained sites, unlike elsewhere.

M. quinquenervia has been widely planted as a street tree and for other purposes in Australia cities, and in many other countries. It has naturalized in the Florida Everglades, where it has become a significant invasive plant. It is also naturalized in islands to the east of Florida, such as the Bahamas and Puerto Rico.

Edibility

Leaves and fruit are not palatable, however the flowers and leaves are sometimes used for herbal teas.

Phytochemistry

While the Melaleuca genus is primarily known for volatile constituents, ie essential oils such as tea tree oil from M. alternifolia, there are also a broad range of non-volatile constituents that provide therapeutic effects when used in the form of leaf extracts or teas. These constituents include polyphenols (tannins and flavonoids), triterpenoids, phytosterols and fatty acids.

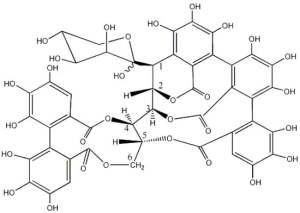

Leaves of M. quinquenervia are rich in tannins. This fact can readily be observed by the reddish colour of the water in coastal rivers and lakes that are fringed by the species. The presence of tannins has been confirmed with analytical studies, which have revealed the presence of gallic and ellagic acids plus the ellagitannin glycosides castalin and grandinin (Moharramet al., 2003). Grandinin has also been found in Melaleuca leucodendron fruit and in some Northern Hemisphere oak trees (Quercus spp.), hence it may be present in wines that are aged in oak barrels. Granadinin has been shown to exhibit potent antioxidant and hypoglycemic properties.

Leaves are rich in flavonoids, including the well-known flavones kaempferol, quercetin, quercitrin and myricetin which also occur as water soluble glycosides. Flowers contain the methyl flavonones kryptostrobin, melanervin and strobopinin.

grandinin, an ellagitannin

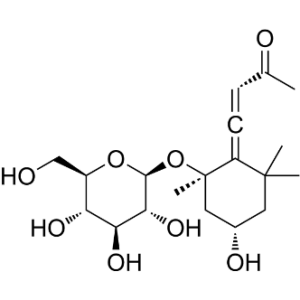

citroside A, a terpene glycoside

Triterpenoids in the leaves include ursolic and oleanolic acids. Five megastigmane (terpenoid) glycosides including roseoside and citroside A have been isolated from leaves of M. quinquenervia. Some of these compounds have been used as ingredients in dietary supplements due to protective effects on the liver, kidneys, and cardiovascular system. Roseoside has also been shown to have anti-inflammatory properties.

Fat-soluble compounds present in leaves and stems include phytosterols (sitosterol, stigmasterol and cholesterol), along with a range of fatty acids such as palmitic, capric, lauric, linoleic and oleic FAs.

Phytochemical analysis of honey produced from M. quinquenervia reveals the presence of the flavonoids luteolin and tricetin along with the simple phenols chlorogenic and p-coumaric acids.

Table 1. Non-volatile constituents of M. quinquenervia

| Class of Compound | Compound Name | Plant Part |

|---|---|---|

| Tannins | Gallic, ellagic acids | Leaves |

| Castalin | Leaves and stems | |

| Castalin | Leaves and stems | |

| Flavonoids | Kaempferol | Leaves and stems |

| Quercetin | Leaves and stems | |

| Quercetin glucopyranoside | Leaves | |

| Quercitrin | Leaves and stems | |

| Myricetin | Leaves and stems | |

| Myricetin rhamnopyranoside | Leaves | |

| Kryptostrobin | Flowers | |

| Melanervin | Flowers | |

| Stroboinin | Flowers | |

| Terpenoids | Ursolic acid | Leaves |

| Oleanolic acid | Leaves | |

| Roseoside | Leaves | |

| Citroside A | Leaves | |

| Sterols | sitosterol | Leaves and stems |

| stigmasterol | Leaves and stems | |

| cholesterol | Leaves and stems | |

| sitosterone | Leaves and stems | |

| Fatty acids – saturated | Palmitic, lauric, capric acids | Leaves and stems |

| Fatty acids – unsaturated | Linoleic, linolenic, oleic acids | Leaves and stems |

Essential oil

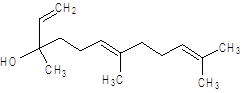

Two distinct chemical forms (chemotypes) of the essential oil have been established. One chemotype is comprised of E-nerolidol (74– 95%) a sesquiterpene alcohol, and linalool, a monoterpene alcohol (14–8%). This chemotype is found mainly within populations from NSW, as well as in the Wide Bay region of Queensland. Oils from the Wide Bay region produce the highest levels of linalool. The compound nerolidol is closely related to nerol from neroli (orange blossom) oil, and it is similarly sweet in odour and gentle in action. Linalool also has a sweet, fruity aroma.

A second chemotype is comprised of 1,8-cineole (up to 75%), the sesquiterpene alcohol viridiflorol (13–66%), α-terpineol (0.5–14%) and β-caryophyllene (0.5–28%). This chemotype is mainly found in Queensland, but occurs less commonly in NSW, where the two chemotypes sometimes overlap. Essential oils produced in Papua-New Guinea and New Caledonia (known as niaouli oil) are also classed within this chemotype. The presence of 1,8-cineole (characteristic of Eucalyptus oil) gives niaouli oil a sharper, more medicinal aroma.

trans-nerolidol – a sesquiterpene alcohol

viridifloral – a sesquiterpene alcohol

Yields of essential oils distilled from the leaves of M. quinquenervia can vary between 0.2 and 3%, and for unknown reasons this seems to vary with latitude. Research findings by Ireland et al. (2002) indicate the southern populations below 25°S yield 1-3% while populations north of this latitude, comprising the second chemotype, have a low yield of 0.1-0.2%.

Table 2. Chemotypes of M. quinquenervia

| Chemotype | Primary Constituents | Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| CTI “nerolina” | E-nerolidol Linalool | Eastern NSW, Wide Bay (Qld) |

| CTII “niaouli” | 1,8-cineole Viridifloral α-terpineol β-caryophyllene | Eastern NSW (less common) Qld Papua New Guinea New Caledonia |

Medicinal uses

Despite the array of phytochemicals present in M. quinquenervia, and the widespread use of the essential oil, there is scant information with respect to the medicinal uses of the plant as a whole. There are anecdotal reports that young leaves bruised and steeped in water have been used for treating colds, headaches and bladder infections.

The high levels of tannins and flavonoids found in its’ leaves indicates the likelihood of therapeutic astringent and anti-inflammatory properties. The traditional infusion mentioned above could have a broader range of benefits, including for digestive and musculoskeletal problems. The presence of terpenoids, including the anti-inflammatory roseoside, suggest that oil or fat-based topical applications could be beneficial for treating wounds and skin lesions.

While essential oils are poorly soluble in water-based preparations such as herbal teas, they are more soluble in aqueous-alcohol extraction media such as fluid extracts and tinctures, widely used by herbalists and naturopaths. Hence such medicinal preparations can provide the therapeutic effects of both non-volatile constituents, outlined above, and of the volatile essential oils, which are discussed next.

Aromatherapy

Aromatherapists in Australia and elsewhere value the therapeutic properties of both nerolina and niaouli essential oils, but for different purposes. Our understanding of essential oil chemotypes is critical to their therapeutic applications. In her “Australian Essential Oil Profiles” text, aromatherapist Deby Atterby describes the nerolina oil aroma as “sweet, fresh and fruity with nice subtle undertones of lavender”. Incidentally one of the main constituents of lavender oil is linalool.

Nerolidol has numerous documented activities, including antimicrobial, antifungal, antibiofilm, antiparasitic, anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive (pain relieving), antitumor and insect repellent. Most of these actions are also found in linalool. Hence nerolina essential oil is useful for treating both bacterial and fungal infections. Atterby reports on her clinical successes in treatment of shingles, anxiety and head lice infections. Nerolidol is highly regarded as a skin penetration enhancer, making the essential oil an effective addition to various topical medications. Studies by Chan et al (2018) demonstrated increase diffusion rate by over 20-fold transdermal delivery of certain drugs. When other herbs or essential oils are combined with nerolidol an increased rate of absorption of other phytochemicals in the formula can be anticipated. Other applications for nerolina include as topical mosquito repellents, in which it may be combined with citronella-based essential oils, to which it imparts a far more refreshing aroma. It has also found applications in perfumery.

As noted above, niaouli essential oil is rich in 1,8-cineole. Giving it a Eucalyptus-like aroma. However, the presence of the sesquiterpenes viridifloral and β–caryophyllene somewhat moderate the sharpness of 1,8-cineole, and some aromatherapists prefer to use niaouli to Eucalyptus oil for treating coughs, colds and headaches. Viridflorol is reported to be a broad-spectrum antimicrobial. The American aromatherapy scientist Kurt Schnaubelt reports the use of niaouli oil (he refers to it as M. quinquenervia viridiflora) for successful treatment of radiation burns in breast radiation therapy, as well as for reducing lymphatic oedemas when used as a massage oil (Schnaubelt, 2011). In fact, there is a separate species, M. viridiflora, which is widespread across Northern Australia and similar in appearance to M. quinquenervia, however it is not reported to contain viridifloral.

Safety

There is no safety data available on the species itself, however it does not contain any known toxic chemicals.

Nerolina and niaouli oils are regarded as unlikely to present any hazard in aromatherapy. Both major constituents of nerolina, nerolidol and linalool, are classified as non-toxic, non-irritant and non-sensitising. 1,8-cineole can be toxic to young children, and inhalation of niaouli oil should be avoided for children under 5 years. Pure essential oils should never be ingested via the mouth.

Other species

There are several other species of paperbark Melaleucas in Eastern Australia (Table 3), most occur in coastal and sub-coastal habitats. The most outstanding is M. alternifolia from northern NSW, the source of tea tree oil, one of the top selling essential oils globally. Most of these species have traditional uses similar to M. quinquenervia, however the essential oil component differs significantly between species. Apart from M. alternifolia, other commonly used essential oils are sourced from M. ericifolia and M. cajuputi.

Table 3. Selection of paperbark Melaleucas

| Species | Common Name | Distribution | Essential oil type |

|---|---|---|---|

| M. alternifolia | Tea tree | NE NSW, SE Qld | Terpenin 4-ol (>30%) |

| M. ericifolia | Rosalina | SE NSW, Vic, Tas | Linalool |

| M. cajuputi | Cajuput | N Qld, NT, WA, PNG, SE Asia | 1,8-cineole |

| M. leucadendron | Weeping paperbark | Qld, NT, WA, PNG | Methyl-eugenol |

| M linariifolia | Snow in summer | Central Coast, NSW | 1,8-cineole, terpenin-4-ol |

| M. stypheloides | Prickly paperbark | NSW, S-central Qld | Sesquiterpenes (very low yield) |

| M. nodosa | Prickly-leaved tea tree | NSW, Qld | 1,8-cineole |

M. viridiflora | Broad-leaved paperbark | Qld, NT, WA, PNG | Variable. Methyl cinnamate |

M. leucadendron

M. alternifolia

M. nodosa

Cultivation

For many coastal and sub-coastal zones of eastern Australia, M. quinquenervia naturally covers vast areas, including on private land. The species is also widely planted in parks, streets and gardens. In areas where wild plants aren’t readily available, M. quinquenervia is easy to propagate and cultivate. It withstands a broad range of soil types, from clay to sand, quite acidic through to neutral pH (4.5-6.5), salt winds and mild frosts. Severe frosts may kill foliage, but the tree will recover due to the presence of epicormal buds. It can withstand waterlogging and floods due to formation of adventitious roots from the trunk. Despite this, M. quinquenervia can withstand dry seasons well, but it requires periodic watering in prolonged droughts, while mulching is also beneficial. It is relatively resistant to insect attacks and diseases.

Trees can be propagated by seed or stem cuttings. Cuttings can be made using the standard methods, strike rates will improve by coating the base of the stems with hormone powder or seaweed concentrate.

Melaleuca seed capsules need to be at least a year old before harvesting, then left to dry out in a warm place for a few days, before the seeds are released. The seeds are tiny, according to the Agroforestry database there are about 2,661,400 viable seeds/kg. Seeds can be mixed with coarse sand for more even distribution, then sown straight into garden beds or seed trays containing propagation media. Within a month or two they should have germinated and developed several leaves, at which stage they are ready for potting on.

Cultivation is not recommended outside of Australia, as the plant may naturalise and become weedy, as it already has in some countries.

Role in agroecology

Being natural inhabitants of wetlands, paperbark Melaleucas should be considered for cultivation in poorly drained areas on farms or in urban settings. Existing stands should be preserved wherever possible. These trees attract nectar-eating birds such as lorikeets and parrots, as well as fruit bats. They also attract a variety of native bees and honeybees. M. quinquenervia can flower for long periods, including during winter when there is a dearth of blossoms, hence they are a valued species for apiarists.

On farms M. quinquenervia is an excellent hedging tree, and the timber can be used for fencing as well as for flooring and posts in building construction and pylons on boat ramps. The wood, including the bark, makes an excellent fuel and good-quality charcoal.

For farmers looking to diversify, essential oil production may be a good option. Tree canopies are dense with leaves, and being evergreen there is a good supply all year round. Having leaves analysed for chemotype is essential before scaling up for commercial distillation. Traders require a certificate of analysis before contracting to purchase essential oils; depending on geographic location (and seed source if setting up a plantation), knowledge of the chemotype is essential. On a non-commercial scale, essential oils, teas and extracts can be produced as medicines, topical salves and insect repellents for the local community, and for livestock.

M. quinquenervia plantations have been established in some countries for restoring degraded lands. With this practice comes the risk of naturalisation and invasiveness, as in Florida, however the practice can be safely applied in the Australian context.

The papery bark is another product with multiple functions. It is traditionally used for making coolamons and shelters, for wrapping food for cooking, lining cradles, to stuff pillows and as emergency bandages.

References

Abdel Bar, F. (2021). Genus Melaleuca – A review on the phytochemistry and pharmacological activities of the non-volatile components. Rec. Nat. Prod. 15(4), 219-242

Atterby, D. (2020). Australian Essential Oil Profiles. AAT Publishing.

Brophy J.J., Craven L.A. and Doran J.C. (2013). Melaleucas: their botany, essential oils and uses. ACIAR Monograph No. 156. Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research.

Chan, W. Tan, L. Chan, K. Lee, L. & Goh, B. (2018). Nerolidol: A sesquiterpene alcohol with multi-faceted pharmacological and biological activities. Molecules 21:529; doi:10.3390/molecules21050529

Ireland B.F., Hibbert D.B., Goldsack R.J., Doran, J.C. & Brophy, J.J. (2002). Chemical variation in the leaf essential oil of Melaleuca quinquenervia (Cav.) S.T. Blake. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 30, 457–470

Lassak, E.V. & McCarthy, T. (1983). Australian Medicinal Plants. Methuen.

Moharram, M. Marzouk, M.S. El-Toumy, S. A. Ahmed, A. A. & Aboutabl, E.A. (2003). Polyphenols of Melaleuca quinquenervia leaves – Pharmacological studies of grandinin. Phytother. Res. 17, 767–773.

Schnaubelt, K. (2011). The Healing Intelligence of Essential Oils. Healing Arts Press.

Orwa C., Mutua A., Kindt R., Jamnadass R. & Simons A. (2009). Agroforestree Database:a tree reference and selection guide version 4.0 (http://www.worldagroforestry.org/af/treedb/)

Tisserand, R. & Balacs, T. (1995). Essential Oil Safety. Churchill Livingstone.

Webb, M. A. (2000). Bush Sense. Australian essential oils and aromatic compounds. Self-published

Websites

https://plantnet.rbgsyd.nsw.gov.au/cgi-bin/NSWfl.pl?page=nswfl&lvl=sp&name=Melaleuca~quinquenervia

https://anpsa.org.au/plant_profiles/melaleuca-quinquenervia/

https://apps.lucidcentral.org/plants_se_nsw/text/entities/melaleuca_quinquenervia.htm

https://integrityhealth.com.au/from-tree-to-tea-meet-my-new-friend-mel/

https://tropical.theferns.info/viewtropical.php?id=Melaleuca+quinquenervia