AUTHOR: Andrew Pengelly, PhD

Backhousia citriodora F. Muell. + Family: Myrtaceae

(NOTE: There is a PDF version of this post available to download HERE.)

Backhousia – named for the botanist James Backhouse

citriodora – from the strong lemon scent of the foliage

Common names: Lemon myrtle, lemon ironwood, sweet verbena tree

Overview

Lemon myrtle is an evergreen tree native to eastern Queensland. The fragrant lemon-scented leaves are rich in essential oils composed mainly of the terpene aldehyde, citral. Both the essential oil and phenolic compounds extracted from the leaves are potent antimicrobials and antioxidants.

Lemon myrtle is widely used in aromatherapy and body care products and is in demand as a food flavour and beverage. Whilst easy to cultivate at home or in plantations, it has become susceptible to the introduced pathogen myrtle rust, which significantly impacts the yield and productivity in plantations.

Description

B. citriodora is an evergreen tree growing to a height of 20m, with a low branching habit. It has opposite, broad lanceolate shaped leaves, glabrous with mostly entire margins. Leaves are typically 5-12cm long, 1-5cm wide, and are distinguished by their characteristic lemon scent upon rubbing.

Creamy white, star-shaped 5-petaled flowers with exserted stamens are arranged in broad clusters, that cover the tree during summer. The calyces persist after the petals fall. The fruit is a dry indehiscent capsule containing several small seeds.

Distribution

B. citriodora is native to the Queensland east coast and hinterland. Distribution is non-continuous, with scattered populations between Brisbane and Gympie, near Rockhampton, the Mackay-Proserpine region and the Atherton Tableland. It typically grows in dry rainforests and sheltered waterways in wet sclerophyll forests.

https://avh.ala.org.au/occurrences/search?taxa=Backhousia%20citriodora#tab_mapView

Edibility

No parts of lemon myrtle are edible in the fresh state, however the dried and ground leaf make an excellent cooking ingredient and spice.

Nutrients

Lemon myrtle is a good source of vitamin E, folate and minerals such as calcium and potassium.

Table 1 Vitamin content of dried lemon myrtle leaves ((Konczak, 2017).

| Vitamin | Molecule | Value (mg/100g D/W) |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin E | lutein | 6.559 |

| α-tocopherol | 0.2 | |

| β-tocopherol | 0.365 | |

| γ-tocopheral | 0.358 | |

| total tocopherol | 21.23 | |

| Folate | 71 |

Table 2. Mineral content of dried lemon myrtle leaves ((Konczak, 2017).

Minerals (mg/100g D/W)

| Fe | Cu | Mn | Zn | Ca | Mg | K | P | Mo | Ni | Co | Na | S |

| 5.8 | 0.47 | 1.28 | 1.05 | 1583 | 188.3 | 1258.7 | 114 | .005 | 0.147 | 0.009 | 19 | 145 |

Phytochemistry

Essential oil

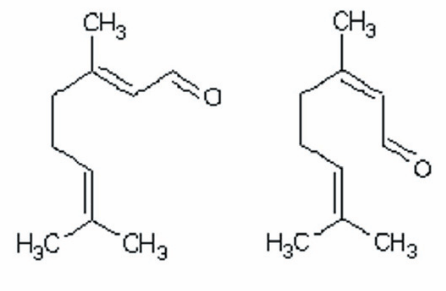

By far the most characteristic compound in lemon myrtle is the terpenoid citral, which occurs as the dominant chemical in the essential oil (95% or above). Citral, a linear monoterpene aldehyde is isomeric, made up of varying proportions of geranial (citral A) and neral (citral B).

The Australian standard for B. citriodora essential oil (4941-2001) also recognizes a number of minor or trace constituents. Following a submission by E.V. Lassek (2012), a revised Australian Standard now allows for the presence of 0.5-2.5% of the monoterpene alcohol geraniol, and the absence of three known adulterants, C8 (n-octyl aldehyde), C9 (n-nonyl aldehyde) and C10 (n-decyl aldehyde), which do not naturally occur in B. citriodora (Standards Australia, 2011). (Table 1).

Table 3. Backhousia citriodora essential oil, typical chemical profile

| Compound | % of essential oil |

|---|---|

| neral | 32.0% + |

| geranial | 44.0% + |

| cis -isocitral | trace – 2.7% |

| trans -isocitral | trace – 4.3% |

| exo -isocitral | trace – 2.0% |

| total citral | 95.0% or above |

| citronellal | trace – 1.0% |

| 6-methyl-5-hepten-2-one | trace – 2.9% |

| 2,3-dehydro-1,8-cineole | trace – 0.9% |

| myrcene | trace – 0.7% |

| linalool | trace – 1.0% |

| geraniol | 0.5-2.5% |

The Australian standard also stipulates the following properties: Relative Density: 0.880-0.910; Refractive Index @ 20°C 1.4880-1.4900; Optical Rotation +3.5-+12.0

Yields of lemon myrtle essential oil from fresh leaves and young stems are as high as 3.2% (w/w) in laboratory glassware, but on average 1.5% (w/w) for commercial steam distillation (Southwell, 2021).

A rare B. citriodora chemotype high in L-citronellal (80% or more) does not conform to the Australian standard and therefore cannot be marketed as lemon myrtle oil. It does however have value as the active ingredient in insect deterrent formulae, and as starting compounds for the synthesis of some terpene compounds and perfumes. In one study, leaves distilled from three trees grown from progeny in the Noosa region of SE Queensland, found the L-citronellal content to range between 85-89%, while the other main compounds present were isopulegol (4-9%), citronellol (2-4%) and myrcene (0.2-0.3%) (Doran et al., 2001).

As a source for citral

Citral is the predominant source of lemon or citrus aromas found in plants. Lemon-scented plants known to contain citral include lemon (Citrus limon), lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus and C. flexuosus), oil of cubebs (Litsea cubeba), lemon verbena (Litsea triphylla), lemon balm (Melissa officinalis) and lemon thyme (Thymus citriodora), while Australia boasts numerous such species including lemon tea tree (Leptospermum petersonii) and lemon ironbark (Eucalyptus staigeriana) (Nhu-Trang et al., 2006; Southwell, 2020).

Citral is an approved food flavouring agent; it is used in the manufacture of perfumes and as a precursor molecule in the production of vitamin A (OECD, 2001). Since the 1920s B. citriodora essential oil has been recognized as producing high quality citral for production of lemon flavoured beverages. There are no grassy notes to the lemon aroma as compared with lemongrass. Of all citral-containing essential oils in plants, lemon myrtle leaves are considered the richest and superior source (Southwell, 2021).

Polyphenols

Kang et al. (2020) investigated the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of polyphenols from B. citriodora leaves extracted in 80% ethanol. Total phenolic (TPC) and flavonoid (TFC) content varied according to the temperature of the solvent and the length of extraction time. The authors determined that the highest TPC levels were obtained after 6 hours extraction at 80°C. These extractions yielded 103 mg GAE/g TPC and 33 mg RE/gTFC (Kang et al., 2020). TPC for water extractions was reported at 75.6 mg GAE/g TPC (Chan et al., 2010). Total phenolic content has been assessed in other studies, however using different measures, namely mg/g (Shim et al., 2020) and tannic acid equivalents (Kim et al., 2017). Hence these values are not equitable with each other.

Polyphenols identified include the flavonoids rutin, luteoloside, catechin with low levels of quercetin, as well as the hydrolysable tannins gallic and ellagic acids (Kang et al., 2020). Along with ellagic acid, Konczak also identified the flavonoids myricetin and hesperetin from aqueous extracts (Konczak, 2017). Sommano, Caffin and Kerven (2013) found the flavonoid narigenin and vanillic acid, a simple phenolic acid. In a Japanese study, several polyphenols were identified in the targeted search for a compound that activates skeletal muscle satellite cells. The compound found responsible for this action of B. citriodora was the ellagitannin casuarinin. Other compounds identified in this study included the flavonoids myricitrin and hyperin (Yamomoto et al., 2022).

Table 4. Polyphenols identified from B. citriodora

| Flavinoids | Tannins |

|---|---|

| rutin | gallic acid |

| luteoloside | ellagic acid |

| catechin | casuarinin |

| quercetin | |

| myricetin | |

| myrecitrin | |

| hesperetin | |

| hyperin | |

| kaempferol | |

| naringenin |

Medicinal Applications

Traditional uses

Surprisingly, there is little recorded use of lemon myrtle among Aboriginal people in the past. In one review it states that leaves were used as an antiseptic, for treating wounds and infections. The leaves are said to have been crushed and applied topically, while infusions were made for inhalation as beverages (Sutton, 2022). Unfortunately, no evidence is provided for these statements.

This situation has changed in the 21st century, when the leaf infusion as a healthy beverage, and the essential oil for therapeutic purposes are now popular among Australians in general, including First Nations people. Australian herbalists, aromatherapists and bushfood pioneers were among the first to document the use of lemon myrtle in this way (Pengelly, 1989; Webb, 2000)

Biomedical Research

Antimicrobial activity

Antimicrobial effects against resistant infections compares favourably with tea-tree oil (Hayes and Markovich, 2002). In their study, minimum inhibitory count (MIC) values were significantly lower for lemon myrtle against bacteria such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa and MRSA, as well as two fungal pathogens including Candida albicans. MIC values for B. citriodora were almost identical to that of citral, which was also tested, indicating that clearly citral is the antimicrobial ingredient at work.

In another study B. citriodora essential oil and a leaf paste were found to inhibit growth of bacteria and fungi, including human pathogens Clostridium, Pseudomonas and a hospital isolate of methicillin resistant S. aureus (MRSA). Interestingly, in this case the essential oil was more potent than citral alone (Wilkinson et al, 2003).

Lin et al. (2022) found lemon myrtle essential oil to be more effective against Gram-positive bacteria (S. epidermidis, S. aureus) than against Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, K. pneumoniae). The essential oil was also effective in preventing and eradicating biofilm formation for these antibiotic-resistant bacteria. The authors conclude their findings demonstrate the potential of the essential oil against human pathogenic bacteria and their biofilms, making it a promising candidate for developing a new treatment or drug adjuvant for nosocomial (hospital-acquired) infections (Lin et al., 2022).

In addition to these findings on the essential oil, polyphenols-rich extracts of B. citriodora have also been found to inhibit pathogenic bacteria. Methanolic extracts of B. citriodora demonstrated potent antibacterial and antifungal effects using a disc diffusion and growth time course assay. These findings established the susceptibility of a broad range of microbes to B. citriodora. Both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria were equally susceptible, though the extracts were weaker than the reference antibiotics tested (Cock, 2013).

Antiviral effects

In a small clinical study, Burke and co-workers demonstrated a 90% reduction of lesions in children infected with Molluscum contagiosum using a 10% olive oil solution of B. citriodora essential oil, compared with no reduction in lesions in the control group (Burke, Baillie & Olsen, 2004). In Japan Hirobe and co-workers demonstrated antiviral effects for B. citriodora leaf capsules against HIV and Cytomegalovirus (Archer, 2004).

Anti-inflammatory effects

For demonstration of anti-inflammatory effects, polyphenols-rich extracts have been used. In a study using LPS-activated murine macrophages, B. citriodora 80% methanol extracts reduced the expression of inflammatory enzymes iNOS and COX-2, accompanied by the decrease of nitric oxide (NO) and prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) levels. The authors identified the tannins gallic and ellagic acid as the active constituents (Guoa, Sakulnarmrata & Konczak, 2014). These results were replicated in a similar study, however in this case the activated macrophages were treated with both aqueous and 80% ethanolic extracts of lemon myrtle (Kim et al., 2017). The findings on decreased NO production by 80% ethanol extracts were again replicated by Kand et al. (2020).

Antioxidant effects

As is the case with anti-inflammatory properties, antioxidant effects of lemon myrtle are closely associated with polyphenol content, from both aqueous and solvent extractions. B. citriodora leaves extracted by 100% ethanol at 80°C for 6 hrs provided optimal conditions for radical scavenging and reducing power – measures of antioxidant activity – which correlated with the total phenolic and flavonoid counts referred to above (Chan et al., 2010). In a study using 80% methanol extracts, lemon myrtle was found to have higher total reducing capacity (FRAP assay) than bay leaf, a known antioxidant. The findings correlated well with the polyphenol content of the extract (Sakulnarmrat and Konczak, 2012).

Lemon myrtle infusion was found to have antioxidant effects comparable to tea (Camellia sinensis). The infusion was more potent than other herb teas tested based on total phenolic content, ascorbic acid equivalent antioxidant capacity, ferric-reducing power, and chelating EC50 (Chan et al., 2010). Lemon myrtle essential oil also provides considerable antioxidant effects. Using the DPPH radical scavenging activity and FRAP methods, the essential oil was more potent than the standard antioxidant ascorbic acid (Lim et al., 2022). Essential oil from the stem also produced antioxidant effects using the DPPH method, the stem oil being just as potent as the leaf oil (Kean et al., 2013).

Metabolic effects

Polyphenol-rich B. citriodora extracts significantly inhibited the glucose regulating enzyme α-glucosidase as well as the blood pressure regulating enzyme, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in vitro. The extract also inhibited the lipid regulating enzyme lipase, though not significantly. Three key imbalances that count towards development of metabolic syndrome are hyperglycemia, dislipidemia and hypertension. Considering the inhibiting effects of lemon myrtle polyphenol-rich extracts on the enzymes responsible for these disorders, this study provides evidence that lemon myrtle has a role to play in the prevention and treatment of metabolic syndrome (Sakulnarmrat and Konczak, 2012).

Other research

In a 12-week human study, a lemon myrtle extract (no details provided) enhanced muscle thickness in older adults engaged in low-load resistance training compared to the control group (Sawada et al., 2024). These effects are attributed to the skeletal muscle satellite cells activating compound casuarinin (Yamomoto et al., 2022).

Use in aromatherapy

Lemon myrtle essential oil has an uplifting, zesty, refreshing lemony aroma. It is ideal for inhalation purposes, whether by diffuser, oil burner or spray. Otherwise, it can be applied topically in diluted form, in the form of lotions, salves or added to herbal tinctures. For topical applications, the pure essential oil should diluted 1-10% in base oil or cream. Bath oils and hydrosols are also popular uses.

Actions attributed to the essential oil include antiseptic, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory, antidepressant, carminative and expectorant. In various forms the essential oil has been used for common cold, influenza, bronchitis, chest congestion, mouth ulcers, dyspepsia, ‘school sores’, herpes and other viral skin lesions, cuts, insect bites, acne, tinea and for promoting sleep (Atterby, 2021; Webb, 2000; Pengelly, 1991).

On the back of some research by Hayes and Markovich, a potent antimicrobial blend of 4:1 teatree/lemon myrtle oil increases the antimicrobial effect of teatree oil and reduces sensitization of lemon myrtle (Hayes & Markovich, 2002).

The essential oil and hydrosol are used in a wide range of household and toiletry products, including hand and body washes, hair and oral care, deodorant, foot spray, surface disinfectant, detergent and spritzer. Lemon myrtle can also be made into a refreshing iced beverage or lemonade. Citral has documented therapeutic uses, including protection from insect bites following oral intake (Saito et al., 2011).

Clinical implications of research

As for most Australian medicinal plants, there is little research on humans to supplement the body of in vitro evidence that has been published. However, given the long-standing reputation for citral as an antimicrobial agent, along with its’ other proven actions, and the high polyphenol content of B. citriodora leaves with their associated antioxidant actions, practitioners should feel confident in using the herb for some of the treatments referred to in this section. There are no safety concerns for use of whole plant preparations.

For those prescribing liquid herbs, lemon myrtle’s excellent flavour lends towards its’ use as a taste corrective in formulas. The herb can be readily made into a tincture, which is an effective way of prescribing given that the aqueous/ethanolic solvent will extract both essential oil and polyphenols. Patients can also be directed to prepare leaf infusions at home. The leaf and leaf oil are both classified as “Listed” medicines by TGA, meaning they can be used in formulating herbal products or used on their own for clinical purposes.

Safety

Aldehydes such as citral are potential skin sensitizers or irritants, and essential oils rich in aldehydes are not to be applied to the skin undiluted. In vitro cytotoxicity testing indicated that both lemon myrtle oil and citral had a toxic effect against human cell lines. A product containing 1% essential oil was found to be non-toxic (Hayes & Markovich, 2003).

According to the Essential Oil Safety Guide, B. citriodora oil is deemed to have only a slight risk of sensitization (Tisserand & Balacs, 1995). Patch testing before use is recommended. Citral-containing oils are contraindicated in patients with glaucoma (Tisserand & Balacs, 1995) Ethanolic extracts exhibited low toxicity in a modified Artemia franciscana nauplii lethality assay (Cock, 2013).

The safety of citral itself has been thoroughly evaluated. Acute toxicity is low in rodents; the oral or dermal LD50 values were more than 1000 mg/kg. The authors concluded that citral is a skin sensitiser and otherwise non-toxic. The skin sensitization only occurs at high concentrations, and is not caused by consumer products (OECD, 2001).

Other species

Backhousia is a genus of trees and shrubs that predominantly grow in eastern Queensland and New South Wales. There are now 13 described species, including two species previously designated to the genus Choricarpa, and excluding B. anisata which has been shifted to the Syzygium genus on the basis of phylogenetic evidence (Harrington et al., 2012, Bowden et al., 2022). One recently described species, B. gundarara, is found in only two known locations in the Kimberley region of Western Australia.

The leaves of all Backhousia species are rich in essential oils, and their aromatic profiles have been reported (Bowden et al., 2022). Other than B. citriodora, none have attracted much attention from aromatherapists or the bushfood industry. The leaves of B. myrtifolia, sometimes referred to as cinnamon myrtle, has been used as a cooking ingredient, as substitutes for spices such as cinnamon and bay leaf.

Cultivation

Provided it is planted at favourable sites, lemon myrtle is relatively easy to grow. It does not enjoy exposure to hot drying winds, and is frost-tender when young, although several specimens are said to be thriving in the Australian National Botanic Gardens, Canberra, where temperatures as low as -8ºC have been recorded. Notably they were planted in the protected Rainforest Gully site.

Lemon myrtle prefers relatively fertile, well-drained soil, in full sun or semi-shade. The trees are adaptable to a wide range of soil types, but they do respond well to mulching and regular fertilising (Mazzorana and Mazzorana, 2016). The species is suitable for hedge planting or for plantation cultivation, in which case row spacing has been determined to enable mechanical harvesting. Spacing of rows at 3m x 1.2m is ideal; this should amount to 2,500 trees per hectare (Mazzorana and Mazzorana, 2016).

The most successful propagation method is by tip cuttings taken in early autumn. Dipping stems in rooting hormone powder or seaweed solutions can boost strike rate. Cuttings and young plants should be kept in a shade house or equivalent and kept moist. Seed propagation is less successful. The very small seed can be mixed with coarse river sand and sprinkled on top of seed raising mixture. Success rate is low, even for commercial propagators.

The CSIRO has established a genebank site for the lemon myrtle industry, following years of collecting seeds and clones from various locations. Following chromatographic analysis of the diverse range of specimens, a cloned variety named “Limpenwood” was selected for commercial producers, for its’ high oil yield and high citral content (Smythe and Sultanbawa, 2016). However, it turns out that this variety is highly susceptible to the recently arrived exotic fungus known as myrtle rust (Lancaster, 2022).

There are virtually no natural predators or diseases of lemon myrtle, the high level of citral in the leaves acts as an excellent deterrent. The situation took a dramatic turn in 2010, with the introduction into Australia of the myrtle rust, initially thought to be caused by the fungal species Puccinia psidii (Carnegie and Lidbetter, 2012). The rust fungus, later designated as Austropuccinia psidii, was found to infect a broad range of plants in the Myrtaceae family, including Backhousia citriodora (Heim et al., 2019). Myrtle rust infections in lemon myrtle plantations have resulted in up to 70 % reduction in biomass yield due to direct leaf loss, reduced leaf size and reduced tree vigour (Lancaster, 2022).

Control of myrtle rust is currently mainly dependent on the use of fungicides. Previously lemon myrtle was highly adapted to organic cultivation and certification, given the lack of natural predators and diseases, but this marketing opportunity is now more limited (Lancaster, 2022).

Role in agroecology

Lemon myrtle could be the most well-adapted species for introduction into Australian agroecological systems. For cash cropping, distillation, medicinal sovereignty, cooking ingredient, herb tea, boutique and value-added product development, inter-row cropping, hedges, brush fences, bird and pollinator attracting, it is unsurpassed. It also has great appeal for urban environments; it is playground friendly, provides aesthetic values for domestic gardens including a most pleasant fragrance and prolific flowers.

Given the myrtle rust issue referred to above, embarking on a plantation venture is not recommended at this time (2025).

References

Archer, D. (2004). Backhousia citriodora F. Muell. Lemon Scented Myrtle : biology, cultivation and exploitation. Toona Essential Oils Pty. Ltd.

Atterby, D. (2021) Australian Essential Oil Profiles. AAT Publishing.

Bowden, B.F., Brophy, J.J. and Jackes, B.R. (2022). Review of the leaf essential oils of the genus Backhousia Sens. Lat. and a report on the leaf essential oils of B. gundarara and B. tetraptera. Plants 11, 1231. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants11091231

Burke, B.E., Baillie, J.E. and Olson R.D. (2004). Essential oil of Australian lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) in the treatment of molluscum contagiosum in children. Biomed Pharmacother. 58(4),245-7. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2003.11.006.

Carnegie, A.J. and Lidbetter, J.R. (2012). Rapidly expanding host range for Puccinia psidii sensu lato in Australia. Australasian Plant Pathol. 41, 13–29

Chan, E.W., Lim, Y.Y., Chong, K.L., Tan, J.B. and Wong, S.K. (2010). Antioxidant properties of tropical and temperate herbal teas. J. Food Composition and Analysis 23, 185–189

Cock, I.E. (2013). Antimicrobial activity of Backhousia citriodora (lemon myrtle) methanolic extracts. Pharmacognosy Communications3(2),58-63

Doran, J.C., Brophy, J.J., Lassak, E.V. and House, A.P. (2001). Backhousia citriodora F. Muell. — Rediscovery and chemical characterization of the L-citronellal form and aspects of its breeding system. Flavour Fragr. J. 16, 325–328 DOI: 10.1002/ffj.1003

Guoa, Y., Sakulnarmrata, K. and Konczak, I. (2014). Anti-inflammatory potential of native Australian herbs polyphenols. Toxicology Reports 1, 385–390

Harrington, M.G., Jackes, B.R., Barrett, M.D., Craven, L.A. and Barrett, R.L. (2012). Phylogenetic revision of Backhousieae (Myrtaceae): Neogene divergence, a revised circumscription of Backhousia and two new species. Australian Systematic Botany 25, 404-417.

Hayes, A.J. and Markovich, B. (2002). Toxicity of Australian essential oil Backhousia citriodora (Lemon myrtle). Part 1. Antimicrobial activity and in vitro cytotoxicity. Food and Chem. Toxicology 40, 535–43.

Hayes, A.J. and Markovich, B. (2003). Toxicity of Australian essential oil Backhousia citriodora (lemon myrtle). Part 2. Absorption and histopathology following application to human skin. Food and Chem. Toxicology 41, 1409–1416

Heim, R.H., Wright, I.J., Scarth, P., Carnegie, A.J., Taylor, D. and Oldeland, J. (2019). Multispectral, aerial disease detection for myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) on a lemon myrtle plantation. Drones 3, 25; doi:10.3390/drones3010025

Kang, E.J., Lee, J.K., Park, H.R., Kim, H., Kim, H.S. and Park, J. (2020). Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of phenolic compounds extracted from lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) leaves at various extraction conditions. Food Sci Biotechnol 29(10), 1425–1432

Kean, O.B., Yusoff, N., Ali, N.A., Subramaniam, V., Ali, N.A. and Yee, S.K. (2013). Chemical composition and antioxidant properties of volatile oil. Proceedings of the ICNP 4, 194.

Kim, P.K., Jung, K.I., Choi, Y.J and Gal, S.W. (2017). Anti-inflammatory effects of lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) leaf extracts in LPS-induced RAW 264.7 cells. J. Life Science 27(9). 986~993

Lancaster, E.K. (2022). The impact and management of myrtle rust (Austropuccinia psidii) in lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) plantations. PhD Thesis. University of Queensland.

Konczak, I. (2017). Health attributes of indigenous Australian plants. In Cherikoff, V. Wild Foods. New Holland Publishers, 140-141.

Lassek, E.V. (2012) Revision of Backhousia citriodora essential oil standard. RIRDC Publication No. 11/137.

Lim, A.C., Tang, S.G., Zin, N.M., Maisarah, A.M., Ariffin, I.A., Ker, P.J. and Mahlia, T.M. (2022). Chemical composition, antioxidant, antibacterial, and antibiofilm activities of Backhousia citriodora essential oil. Molecules 27, 4895. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules27154895

Mazzorana, G. and Mazzorana, M. (2016). Cultivation of lemon myrtle. In Sultanbawa. Y. and F. (eds.) Australian native plants. Cultivation and uses in the health and food industries. CRC Press.

Nhu-Trang T.T., Casabianca H. and Grenier-Loustalot M.F. (2006). Authenticity control of essential oils containing citronellal and citral by chiral and stableisotope gas-chromatographic analysis. Anal Bioanal Chem. 386(7-8), 2141-52.

OECD. SIDS Initial Assessment Report, CITRAL CAS N_:5392-40-5 for 13th SIAM (Switzerland, 6–9 November 2001). Available online: https://hpvchemicals.oecd.org/UI/handler.axd?id=0ea83202-3f4f-4355-be4f-27ff02e19cb9 (accessed on 21 January 2025).

Pengelly, A. (1991). Australian medicinal plant: Backhousia citriodora. Australian J. Med. Herbalism 3(3)

Saito, Y., Sohei, I., Koltunow, A.M. and Sakai, H. (2011). Crystallization and preliminary X-ray analysis of geraniol dehydrogenase from Backhousia citriodora (lemon myrtle). Acta Cryst. F67, 665–667

Sakulnarmrat, K. and Konczak, I. (2012). Composition of native Australian herbs polyphenolic-rich fractions and in vitro inhibitory activities against key enzymes relevant to metabolic syndrome. Food Chem. 34, 1011-1019)

Sawada, S., Nishino, A., Honda, S., Tominaga, Y., Makio, S., Ozaki1, H. and Machida, S. (2024).Effect of resistance training and lemon myrtle extract on muscle size of older adults: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Functional Foods in Health and Disease 14(12), 934-946

Smythe, H. and Sultanbawa, Y. (2016). Unique flavours from Australian native plants. In Sultanbawa. Y. and F. (eds.) Australian Native Plants. Cultivation and Uses in the Health and Food Industries. CRC Press.

Sommano, S., Caffin, N. and Kerven, G. (2013) Screening for antioxidant activity, phenolic content, and flavonoids from Australian native food plants. Int. J. Food Properties 16, 1394–1406

Southwell, I. (2021). Backhousia citriodora F. Muell. (lemon myrtle), an unrivalled source of citral. Foods 10, 1596. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods10071596

Standards Australia (2011). Amendment No. 1 to AS 4941—2001 Oil of Backhousia citriodora, citral type (lemon myrtle oil).

Sultanbawa, Y. (2016). Lemon Myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) Oils. In: Preedy, V.R. (Ed.), Essential oils in food preservation, flavor and safety. Academic Press, 517–521.

Sutton, P. (2022). Aboriginal uses of Australian herbs: Exploring traditional knowledge, medicinal practices, and their role in modern applications. Australian Herbal Insight 5(1) 1-5 https://doi.org/10.25163/ahi.519944

Tisserand, and Balacs, T. (1995). Essential oil safety guide. Churchill Livingstone

Webb, M. (2000). Bush Sense. Griffen Press.

Wilkinson J.M., Hipwell M., Ryan T. & Cavanagh HM. (2003) Bioactivity of Backhousia citriodora: antibacterial and antifungal activity. J Agric Food Chem. 12 51(1), 76-81

Yamomoto, A., Honda, S., Ogura, M. Kato, M., Tanigawa, R., Fujino, H. and Kawamoto, S. (2022).Lemon myrtle (Backhousia citriodora) extract and its active compound, casuarinin, activate skeletal muscle satellite cells in vitro and in vivo. Nutrients 14, 1078

Web sources

https://www.anbg.gov.au/gnp/gnp14/backhousia-citriodora.html

https://anpsa.org.au/plant_profiles/backhousia-citriodora/

https://www.downunderenterprises.com/lemon-myrtle