By Andrew Pengelly, PhD

(NOTE: There is a PDF version of this detailed post available to download HERE.)

Tetragonia tetragonoides (Pall.) Kuntze. (syn. T. tetragonioides) Family: Aizoaceae

Tetragonia – from the Greek, tetra, four and gonia, angle, referring to the 4-angled fruits

tetragonoides – similar to the genus Tetragonia (the species was originally placed in the genus Demidovia) (ANPS, 2024)

Common names: Warrigal greens, New Zealand spinach, Botany Bay greens, tsuruna (Japan)

Overview

Known as Warrigal greens and New Zealand spinach among other names, T. tetragonoides is a low growing, straggling herb whose bright green leaves are edible. It is a well-known coastal plant in Eastern Australia, but it also inhabits inland sites, and the distribution spreads into Asia as far north as Japan.

Warrigal greens are quite nutritious, being high in iron and other minerals. The leaves also contain, oxalates, hence it is widely recommended they not be eaten raw. While there is little evidence T. tetragonoides was a significant edible or medicinal plant within Aboriginal communities, it does have a history of medicinal use in Japan and Korea.

The plant is easy to propagate and grow, however it may need to be contained to prevent spreading.

Description

Perennial, semi-prostrate herb with straggling habit, distinctive triangular or diamond-shaped fleshy leaves to 10cm in length, glossy green on the upper side, light green below. Leaves are arranged alternately on long, succulent stems. Flowers are small, greenish yellow, with 4 petals and up to 22 stamens. They occur in the leaf axils for most of the year. Fruit is a green nut, hard, with short horn-like projections.

Distribution

Concentrated along the east coast from Tasmania to central Queensland, T. tetragonoides is also found in scattered inland locations, including in South and Western Australia, on sandy soil and salt marshes. The species occupies both islands of New Zealand and several Pacific Islands. It is found in Asia, as far north as Japan. In many countries it has become naturalised following cultivation.

https://avh.ala.org.au/occurrences/search?q=taxa%3A%22Tetragonia+tetragonoides%22#tab_mapView

Edibility

Warrigal green leaves have long been considered one of, if not the best, source of greens from the Australasian continent. The greens were ‘discovered’ by Captain Cook when circumnavigating New Zealand (hence the name New Zealand spinach), to be eaten by his crew as a means of preventing scurvy (Cambie & Ferguson, 2003). It is most often used as a substitute for English spinach or silverbeet.

As Table 1 reveals, T. tetragonoides is highly nutritious, being a good source of iron, along with other minerals and vitamins. Mature leaves are high in oxalates, hence they should be cooked or blanched before eating. Young leaves may be eaten raw.

Nutrients

Table 1. Vitamin and mineral content of T. tetragonoides leaf

| Nutrient | Item | Quantity (Dried weight) |

|---|---|---|

| Protein | 18.25% | |

| Carbohydrate | 50.65% | |

| Fat | 4.15% | |

| Energy | 14 kcal/100 g | |

| Fibre | 13.94% | |

| Vitamin A | β-Carotenoid Retinol equiv | 14.5mg/100g |

| Vitamin B | Thiamin | 0.16mg/100g |

| Riboflavin | 0.32 mg/100g | |

| Niacin | 0.8 mg/100g | |

| Folate | ||

| Vitamin B6 | 0.237 mg/100 g of fresh weight | |

| Vitamin C | Ascorbic acid | 50.55mg/100g |

| Vitamin E | 1.23 mg/100 g of fresh weight | |

| Minerals | Magnesium | 35.97 mg/100g |

| Calcium | 37.54 mg/100g | |

| Iron | 4.54 mg/100g | |

| Phosphorus | 106.6 mg/100g | |

| Sodium | 72.7mg/100g | |

| Potassium | 270.65 mg/100g | |

| Zinc | 1.29 mg/100g | |

| Other | Oxalates | 391mg/100 g of fresh weight |

References: Friday & Igwe (2021); Onoiko & Zolotareva (2024)

Phytochemistry

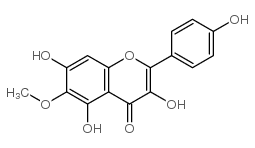

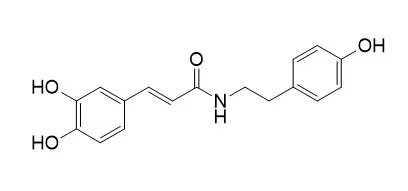

In addition to an impressive level of nutrients, T. tetragonoides contains phytochemicals with therapeutic potential. The main groups represented are polyphenols, dominated by 6-methoxykaempferols (a class of flavonols known for their potent antioxidant effects), along with phenolic acid esters and glycosides (Lee et al., 2008; Onoiko & Zolotareva, 2024). A lesser-known group of compounds, lignan amides contain both phenolic and amino acid derivatives (Choi et al., 2016). Also present are hydroxycinnamic acids, including ferulic acid, a wound healing agent (Williams, 2020).

Non-phenolic compounds present include methyl linoleate, an unsaturated fatty acid (Choi et al., 2016), the carotenoids lutein, violaxanthin, neoxanthin (Onoiko & Zolotareva, 2024), polysaccharides (Kato et al, 1985) and cerebrosides (Okuyama &Yamazak, 1983). Cerebrosides are complex compounds derived from sphingolipids, lipid chains that occupy cell membranes in plants and animals. Ceremides occur when springolipids link up with a fatty acid. When these combine with glucose or another sugar, glycolipids such as cerebrosides are formed. Cerebrosides are constituents of the myelin sheath in animals, but they are much less common in plants. They are known to have antiulcer and other therapeutic benefits for humans (Okuyama & Yamazak, 1983).

Alkaloids and saponins have also been reported from T. tetragonoides, however there are scant details of these compounds reported in the research literature (Friday & Igwe, 2021).

Medicinal uses

While traditional uses for warrigal greensare mainly concerned with edible and nutritive values, the presence of an impressive range of phytochemicals points to potential therapeutic applications, some of which are backed by research. For example, carotenoids, methoxyflavonols and other polyphenols present in the plant are all regarded as potent antioxidants, and diets high in antioxidants are strongly associated with cardiovascular health and prevention of many chronic and age-related disorders (Choi et al., 2016; Onoiko & Zolotareva, 2024). Ferulic acid is an ingredient in many skin care products, being protective against sun damage, acne, discolouration and other disorders of the skin (Williams, 2020).

Carotenoids, in particular xanthophylls such as those found in T. tetragonoides, are particularly important for eye health, being preventative for cataracts and age-related macular degeneration, a major cause of blindness (Onoiko & Zolotareva, 2024).

Inhibition of free oxygen radicals (ie antioxidant effects) are correlated with the total phenolic content of warrigal greens, however boiling the greens was found to significantly reduce the antioxidant property (Amaro et al., 2011).

Biomedical research

Research and anecdotal reports from Japan suggest warrigal greens are effective in the treatment of both stomach ulcers and stomach cancer (Kato et al., 1985). Cerebrosides from T. tetragonoides, as well as other plants such as Medicago sativa, have been shown to have antiulcerogenic effects on stress-induced ulcers in mice (Okuyama & Yamazak, 1983).

Water-based extracts from T. tetragonoides inhibited the expression of inflammatory mediators including TFN-α and tryptase in cell cultures (mast cells) (Kang et al., 2005). The anti-inflammatory effect may be linked to the presence of water-soluble polysaccharides in the plant, two of which were found to reduce inflammation and swelling in carrageenan induced rodent paw oedema in a separate study, by as much as 37%. The polysaccharides had a branched structure with 1-6 glucose linkages (Kato et al., 1985). In a more recent study, anti-inflammatory activity of hexane and polysaccharide fractions was confirmed by the inhibition of the inflammatory mediators lipopolysaccharide (LPS), induced nitric oxide (NO) and the interleukin (IL)-1β production in mice (Choi et al., 2015). These combined findings provide evidence of anti-inflammatory actions of T. tertragonoides, due at least in part to the presence of branched polysaccharides.

Antimicrobial action against gram-positive and gram-negative pathogenic bacteria for solvent extractions of T. tetragonoides were conducted in China. The investigators found relatively strong inhibition of bacteria growth with MIC values between 15.6 and 1,000 μg/mL (Choi et al., 2008).

Extracts of T. tetragonioides have been shown to inhibit enzymes associated with blood sugar regulation, including α-amylase activity in the saliva and pancreas and α-glucosidase (from yeast), pointing to the anti-diabetic potential of warrigal greens (Choi et al., 2008b). These findings were further validated in ovariectomized rats; those treated with a 70% ethanol extract of T. tetragonoides had significantly lower serum glucose and insulin concentrations compared to controls (Ryuk et al., 2017). While there was no evidence of oestrogenic effects, the authors surmise that T. tetragonoides may be a useful agent for treating menopausal symptoms in a similar way to the selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) (Ryuk et al., 2017).

A T. tetragonoides extract (70% ethanol) has also been found to have androgen-inhibiting effects. In vitro studies demonstrated inhibition of testosterone, while testosterone and luteinising hormones were suppressed in a polycystic ovary syndrome (POCS) rat model (

Pyun et al., 2018), suggesting the extracts could be a useful treatment for POCS, a leading cause of female infertility.

Clinical considerations

There is no record of warrigal greens being used for medicinal purposes in Australia, either in customary or biomedical settings. However, in Japan and Korea not only is there evidence of traditional use for stomach disorders and other conditions, but there is also a body of research literature that points to potential therapeutic benefits for diabetes, menopausal symptoms, PCOS and other conditions marked by hormonal imbalance. Given the biomedical and phytochemical research has to date been largely conducted outside of Australia, there is no certainty that Australian plants contain the same phytochemical profile as those in northern Asia, although there are unlikely to be major differences.

For health practitioners in Australian and other non-Asian countries, P. tetragonoides

extracts are not readily available. The challenge for the complementary medicine research community in Australia is for the species to acquire listing status on the Australian Register of Therapeutic Goods (ARTG). Initiation of safety and phytochemical studies would go a long way towards achieving this. Many of the therapeutic benefits outlined above were achieved using 70% ethanol extracts – these are very simple to manufacture. The potential reward is for a local plant of widespread distribution to play a future role in addressing some common health disorders for which there are currently limited treatments available.

Other species

Tetragonia speciesin Australia are distributed either in coastal areas or along inland salt pans. All are edible, with varying degrees of saltiness. Apart from T. tetragonoides, other species include:

T. implexicoma, or bower spinach, inhabits the coastal zones of Tasmania, Victoria, SA and WA, as well as New Zealand. It has small red edible fruit.

T. moorei, found only in the arid and semi-arid zones of Central Australia

T. eremaea or annual spinach, is concentrated in arid regions of SA and WA.

T. decumbens or sea spinach is a South African species that is naturalised in some coastal regions of NSW, WA and SA.

Cultivation

Warrigal greens are easy to cultivate. They will grow in any sunny well-drained soil, and they are relatively salt and drought resistant. A stress-responsive gene known as α-galactosidase has been isolated from Japanese plant specimens. The gene was expressed most strongly in plants subjected to drought conditions compared to other stressors (Hara, Tokunaga & Kuboi, 2008).

The greens can spread to two metres or more, sometimes becoming weedy if left unchecked in the vegetable garden. Being perennial, and without a dormant phase (except in very cold climates), they produce edible greens all year round, being sometimes referred to as a summer spinach. There are few or no known diseases or insect pests, however it has been known to host the beet cyst eelworm, a pest of some green vegetable crops (Buddenhaggen, 2024).

Propagation is by seed or tip cuttings during spring or early summer. Seed should be soaked in hot water overnight before sowing. It will germinate in 2-3weeks. Self-propagated seedlings can be readily potted up or transplanted. The plant is widely available from nurseries, while the seed can be readily accessed via the internet. It can be grown as a pot herb.

Role in agroecology

There is a limited demand for Warrigal greens in restaurants that feature bush foods, hence there may be scope for cultivating it as a cash crop. In an agricultural setting, it makes an excellent cover crop, particularly in vineyards and orchards, as it forms a thick mat of leaves which suppress weeds and require little maintenance, other than cutting them back if necessary. Excess leaves and stems make excellent compost. The mat of leaves can provide shelter for lizards, frogs and other small animals.

References

Amaro, L.F., Almeida, I.F., Ferreira, I.M & Pinhe, O. (2011) Antioxidant activity and total phenolic compounds of New Zealand spinach (Tetragona tetragonioides): Changes during boiling. Culinary Arts and Sci. VII, 67-74

Australian Native Plant Society (2024). Tetragonia tetragonioides. https://anpsa.org.au/plant_profiles/tetragonia-tetragonioides/

Buddenhaggen, C. (2024). Tetragonia tetragonioides (New Zealand spinach). CABI Compendium 52942 https://doi.org/10.1079/cabicompendium.52942

Cambie, R.C. and Ferguson, L.R. (2003). Potential functional foods in the traditional Maori diet. Mutation Research 523–524, 109–117

Choi, H.J., Park, M.R., Kang, J.S., Choi, Y.W., Jeong, Y.K. and Joo, W.H. (2008) Antimicrobial Activity of Four Solvent Fractions of Tetragonia tetragonioides. Cancer Prev Res 13, 205-211.

Choi, H.J., Kang, J.S., Choi, Y.W., Jeong, Y.K., and Joo, W.H. (2008b) Inhibitory activity on the diabetes related enzymes of Tetragonia tetragonioides. Korean J. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 23, 419–424

Choi, H.J., Yee, S.-T., Kwon, G.-S. and Joo, W.H. (2015) Anti-inflammatory and anti-tumor effects of Tetragonia tetragonoides extracts. Microbiol. Biotechnol. Lett., 43, 391–395.

Choi, H., Cho, J., Jin, M., Lee, Y., Kim, S., Ham, K. and Moon, J. (2016). Phenolics, acyl galactopyranosyl glycerol, and lignan amides from Tetragonia tetragonioides (Pall.) Kuntze Food Sci Biotechnol 25(5) 1275-1281

Friday, C. and Igwe, O. (2021). Phytochemical and nutritional profiles of Tetragonia tetragonioides leaves grown in southeastern NigeriaChemsearch J 12(2), 1-5

Hara, M., Tokunaga, K. and Kuboi, T. (2008). Isolation of a drought-responsive alkaline alpha-galactosidase gene from New Zealand spinach. Plant Biotechnol. 25, 497–501

Kang, O., Choi, Y., Park, H. Tae, J…………………………..Lee, Y. (2005). Inhibitory effect of Tetragonia tetraonoides water extract on the production of TNF-α and tryptase in trypsin-stimulated human mast cells. Nat. Product Sci. 11(4), 207-22.

Kato, M., Takeda, T., Ogihara, Y. Shimizu, M., Nomura, T. & Tomita, Y. (1985). Studies on the structure of polysaccharide from Tetragonia tetragonoides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 33(9), 3675-3680

Lee, K.H., Park, K.M., Kim, K.R., Hong, J., Kwon, H.C. and Lee, K.R. (2008). Three new flavonol glycosides from the aerial parts of Tetragonia tetragonoides. Heterocycles 75, 419–426.

Okuyama, E. and Yamazak, Y. (1983). The principles of Tetragonia tetragonoides having anti-ulcerogenic activity. II. Isolation and structure of cerebrosides. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 31(7), 2209-2219.

Onoiko, O.B. and Zolotareva, O.K. (2024)Bioactive compounds and pharmacognostic potential of Tetragonia tetragonioides. Biotechnologia Acta 17(1), 29-42

Pyun, B., Yang, H., Sohn, E. Yu, S.Y., Lee, D., Jung, D.H., Ko, B.S. and Lee, H.W. (2018) Tetragonia tetragonioides (Pall.) Kuntze regulates androgen production in a letrozole-induced polycystic ovary syndrome model. Molecules 23, 1173; doi:10.3390/molecules23051173

Ryuk, J.A., Hye, B.S., Lee, W., Kim, D.S., Kang, S., Lee, Y.H. and Park, S. (2017). Tetragonia tetragonioides (Pall.) Kuntze protects estrogen deficient rats against disturbances of energy and glucose metabolism and decreases proinflammatory cytokines. Experimental Biol. and Med. 242, 593–605.

Williams, C. (2020). Bush Remedies. Rosenberg.

Web Sources

https://anpsa.org.au/plant_profiles/tetragonia-tetragonioides/

https://tuckerbush.com.au/warrigal-greens-tetragonia-tetragonioides/

https://www.cabidigitallibrary.org/doi/full/10.1079/cabicompendium.52942